Cryptocurrency mixers and the illicit activity often associated with them regularly make headlines. To the casual observer, the frequency of these attention-grabbing stories can give the impression that crypto mixing is far more prevalent than it is. Data tells us mixer transactions make up a shockingly small fraction of overall crypto activity.

Since Bitcoin’s inception, blockchain technology has been closely associated with the dark web, money laundering, tax evasion and worse. Just last year millions in bitcoin were paid in ransom to the hackers of the Colonial Pipeline, further perpetuating the public’s belief about the underground world of blockchain-based currencies.

In reality, being a distributed, public ledger makes the Bitcoin and Ethereum blockchains overly transparent.

This article is part of CoinDesk’s Privacy Week series.

By just knowing a public wallet address, one can track all past and future transactions of the account. Any association between exchanges, entities or doxxed individuals – private individuals who have had publicly revealing identifying information about them published online, either intentionally or unintentionally – could give insight into who is doing what in each transaction.

In one respect, transparency is quite refreshing as societal and ecosystem norms are often imposed on venture capital firms, project founders and other members of the crypto community. However, the need for privacy exists if crypto is ever to take on a mainstream role in payments, finance and banking.

The Bitcoin and Ethereum communities understood the downside of transparency and have since built infrastructure to allow users to opt-in to further privacy through potential “unregulated or controversial” technology.

Read More: Bitcoin Mixers: How Do They Work and Why Are They Used?

Bitcoin mixers: In the beginning

Early on, Bitcoin privacy was achieved through centralized mixing services that required trust in third parties. A user would send bitcoin to a company that “mixed” or “tumbled” the funds with other depositors’ bitcoin and then sent back an equivalent amount of mixed bitcoin on the other end. Users who wanted privacy were, in effect, exchanging their bitcoins for other bitcoins that couldn’t be associated with their own.

There was a substantial risk in using these mixing services. Users had to entrust their coins to the third-party mixing platform and believe that they’d get their funds back. Bitcoiners especially took issue with that idea since the Bitcoin protocol counts trustlessness as one of its core tenets. Centralized services were also at risk of being shut down due to regulatory action, and many early mixers were shut down.

In 2013, Greg Maxwell proposed CoinJoin, a transaction privacy method that involved no changes to Bitcoin itself. A CoinJoin takes advantage of how Bitcoin transactions are structured with a bitcoin input from a user, a signature that allows that input to be sent, and an output location for that bitcoin to end up. The signatures are unique for each input. Although these inputs usually come from the same user, they are not required to be. This is how CoinJoin works: Many users can contribute multiple inputs to a transaction where they ultimately send bitcoin to themselves on the other side, but the details are obfuscated due to the unknown number of parties who contributed inputs.

CoinJoins have always worked on Bitcoin, but there wasn’t always an easy way for users to collaborate and carry out a CoinJoin to enable privacy. Now, there are bitcoin wallets like Wasabi Wallet and Samourai Wallet that allow users to implement PayJoins, an implementation of CoinJoin, within the wallet, making privacy available to all.

Bitcoin mixer usage

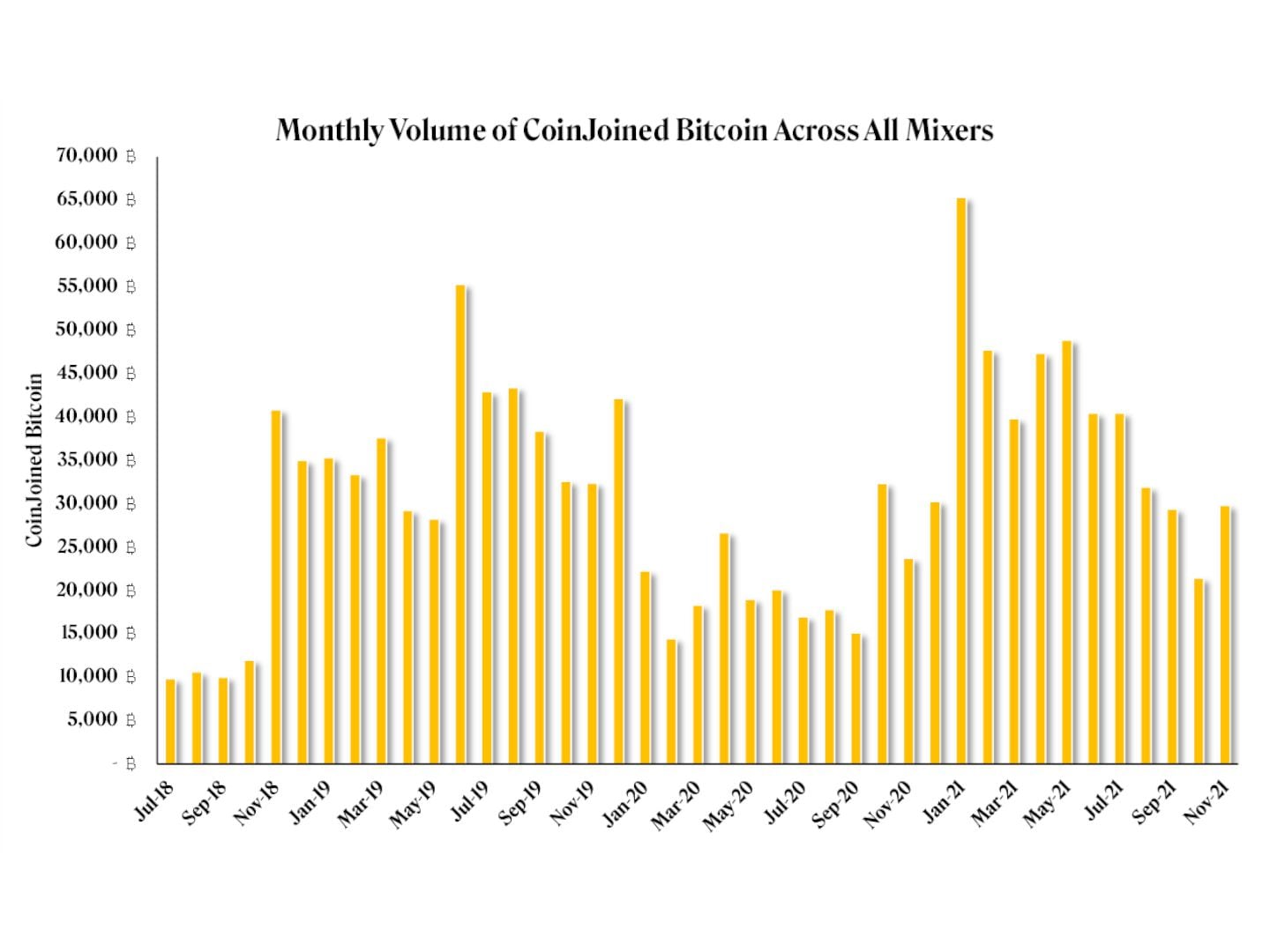

However, even though these privacy options have been around since 2018, the volume data suggests the penetration of CoinJoins has not increased much since the early days. Although more bitcoin has been CoinJoined each year, the highest volume month was just over 65,000 BTC in January 2021 (worth about $2.3 billion, on average), a scant 0.35% of the total bitcoin transacted in that month.

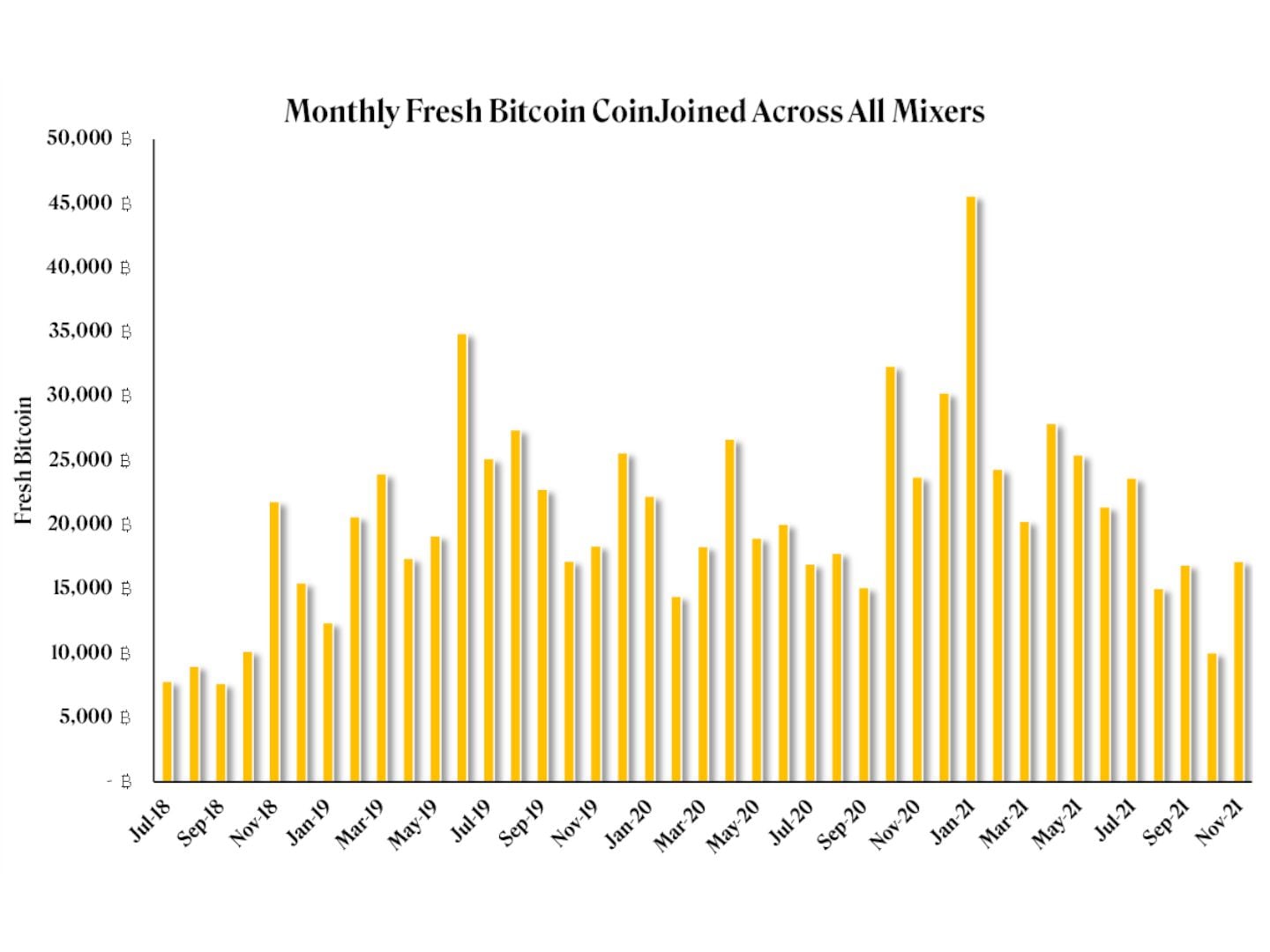

The same phenomenon shows itself when considering “Fresh Bitcoin” – a metric that describes new bitcoins that use a CoinJoin that have never been mixed before.

We can see that these data sets look strikingly similar, but the Fresh Bitcoin metric likely provides a more realistic view for demand growth for CoinJoins, given some users opt to mix the same bitcoins multiple times in order to increase privacy and mathematically guarantee untraceability. The number of Fresh Bitcoins CoinJoined in January 2021 was closer to 45,000, or 0.25% of the total bitcoin transacted in that month.

Part of this overall lack of adoption can be due to exchanges blocking withdrawals to privacy-preserving bitcoin wallets, such as Wasabi, which would naturally suppress demand for CoinJoin as mixing would disrupt the fungibility of the owner’s bitcoin. That is, the bitcoin that went through a mixer would be “tainted” and treated differently by the exchange than other bitcoin.

The future of bitcoin mixers

Taproot was an important upgrade made to the Bitcoin protocol that was implemented late last year. Taproot enabled a handful of potential usability and privacy improvements, with the addition of Schnorr signatures an address type to Bitcoin that makes types of transactions look the same, making blockchain forensic analysis more difficult for multisignature transactions.

As it relates to mixer traffic, however, Taproot in its current state does not improve the privacy of CoinJoins because their inputs are single signature.

That said, Taproot’s activation sets the groundwork in order for cross-input aggregation (CISA) in the future, which would allow for improved privacy and efficiency of CoinJoin transactions. Digital signatures are the critical piece that allows CoinJoins to work. If CISA makes it into the Bitcoin protocol, the many signatures needed in a CoinJoin transaction could be combined and aggregated into one, which could boost scalability and make the process cheaper.

Tornado Cash: A mixer for Ethereum

The most popular mixer on Ethereum takes a different approach than CoinJoin because it is built and deployed on the application layer. Tornado Cash allows ETH holders to deposit a sum of their token balance into a non-upgradable smart contract that gives them an encrypted note. Using the encrypted note, the user can withdraw the funds from another Ethereum address in a single or multiple transactions.

One step further, Tornado Cash allows third parties called “relayers” to send that encrypted note verifying the withdrawal transaction to application users. In return for passing the note, relayers receive a small fee. The relayer system allows users to have their funds trustlessly withdrawn into a new wallet, without needing ETH in the new wallet to pay for the claim transaction because the relayers also take care of covering that cost on their behalf.

It is important to note that relayers are not able to access any transaction data beyond paying the transaction fee, stopping them from altering the destination of the claimed funds.

At the end of the process, the user who deposited their assets into Tornado Cash now has them in a fresh wallet, leaving behind a very difficult trail to follow. In turn, the relayer takes a small fraction of the deposit to pay for the claim transaction and reward them for their service.

Tornado Cash usage

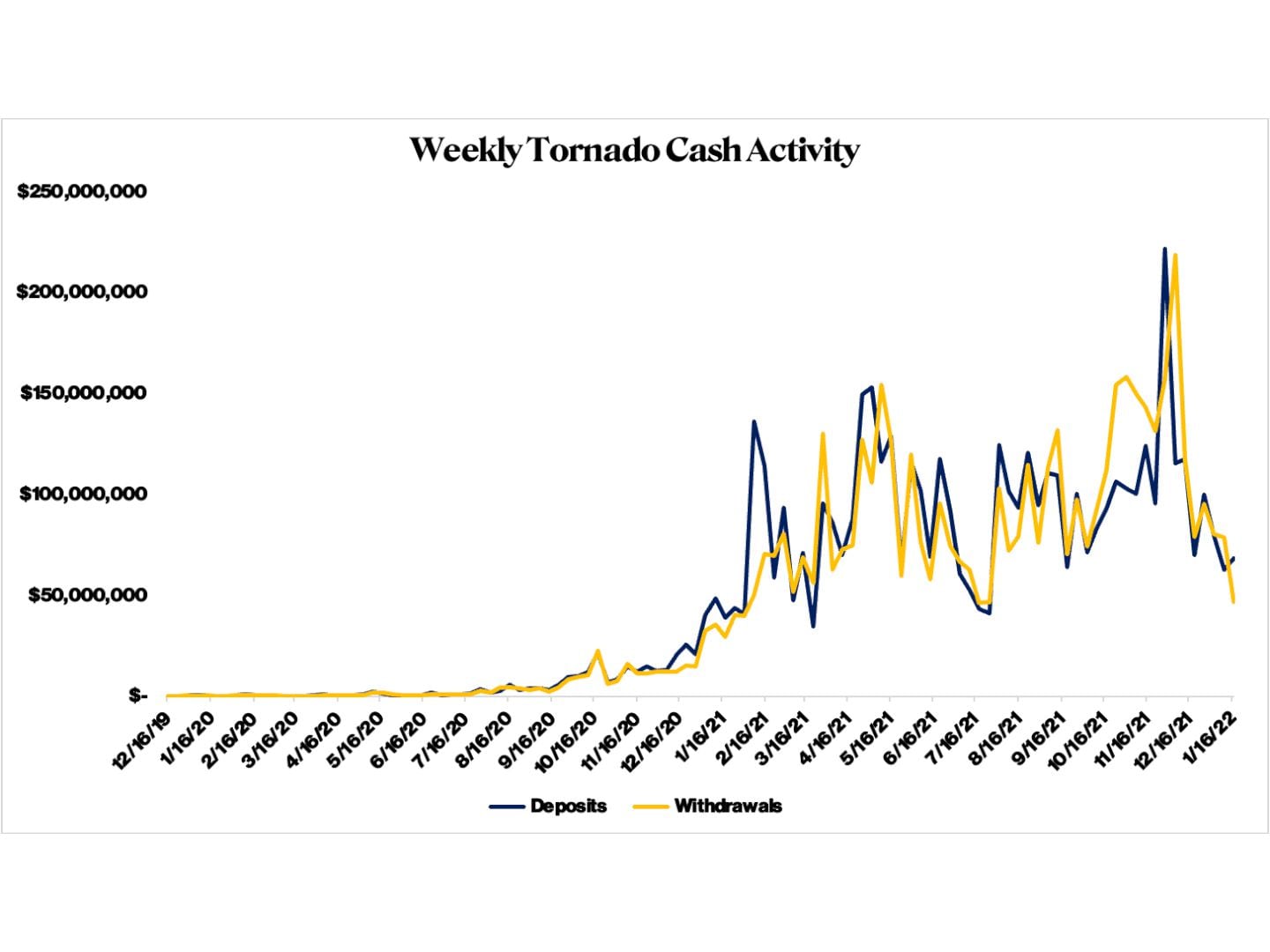

Tornado Cash version 1 has been live since the end of 2019 and has processed 2.4 million ETH and $5.1 billion U.S. dollar-pegged stablecoins at the time of writing, according to data from Dune Analytics and Etherscan. Most often used was the fixed deposit of 10 ETH, with the contract seeing 13,819 transactions since December 2019.

November of last year was the largest month for Tornado in terms of volume, processing over $200 million ETH and stablecoin withdrawals in the last week of the month. However, during December the application released a new product dubbed Nova. The upgrade allows users to deposit arbitrary amounts of assets instead of the outdated, tiered and fixed deposit limits. Nova has seen some adoption with 673 wallets depositing 633 ETH in the new platform in less than a month.

While Ethereum’s most popular mixer is often publicized for its use after decentralized finance (DeFi) exploits or nefarious activities, the application appears to be growing in popularity among everyday users concerned with operational security (opsec) and privacy. Recent compliance integrations even allow the application to generate a report on whether an address’s use of Tornado Cash was in relation to any known exploits or laundering, so law-abiding users can access the technology without drawing unnecessary suspicion.

Read More: Crypto.com’s Stolen Ether Being Laundered via Tornado Cash

The double-edged sword of crypto mixers

The adoption of DeFi, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and bitcoin have gone parabolic over the past year, making illicit activities a smaller percentage of overall crypto transactions than ever. A recent Chainalysis report revealed that even as the notional value of illegal activity hit $14 billion, illicit transactions only made up 0.15% of all cryptocurrency volume during 2021.

Mixers will continue to support those with ill intentions – but that is the double-edged sword of privacy and decentralization. Not only is anyone allowed to access and use blockchain wallets, developers are allowed to build and deploy any product they deem fit on top of smart contract platforms like Ethereum.

As it stands now, regular bank accounts provide us a high level of personal privacy from our friends and family. It is exceedingly difficult to find out how much money someone has in their bank account even if you know a lot of identifying information about that person.

With cryptocurrencies, on the other hand, if your wallet address becomes known, your balance and all your crypto activities can become known. Bitcoin and Ethereum should be able to provide that privacy at a minimum, and the use of privacy-focused technologies like mixers provides that option to everyday crypto users.

However promising mixers are for privacy, the data shows that users are still not taking advantage of what they have to offer. Meanwhile, the mainstream narrative points to mixers enabling illicit activity rather than the potential benefits they may provide to individuals.

More education on the topic, and less stigmatization of mixers themselves, could go a long way toward improving personal financial privacy.